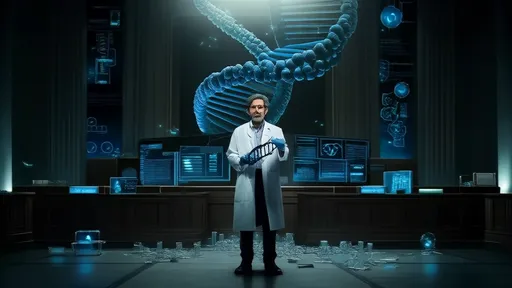

In the rapidly evolving landscape of neuroscience and genetic engineering, a provocative new metaphor has emerged at the intersection of trauma studies and biotechnology. The concept of "trauma memory editing" – borrowing CRISPR's precision-cutting imagery – is sparking both excitement and ethical debates within academic circles. This cognitive framework suggests our brains might possess molecular mechanisms analogous to genetic editors, capable of selectively modifying traumatic memories without erasing their contextual significance.

Researchers at several leading institutions have begun exploring how the CRISPR metaphor reshapes our understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment. Unlike traditional therapeutic approaches that aim to suppress or overwrite traumatic memories, this new paradigm proposes targeted memory reconsolidation – a process where traumatic memories are temporarily destabilized and then modified with new, less distressing information. The biological parallel lies in how CRISPR-Cas9 precisely snips DNA strands before cellular repair mechanisms introduce changes.

The metaphor gains traction from recent discoveries about memory's physical basis. Neuroscientists have identified engram cells – neural ensembles that physically encode specific memories. These cells demonstrate remarkable plasticity during recall, creating what researchers call "reconsolidation windows." During these brief periods, the molecular structure of memories becomes temporarily labile, much like the unzipped DNA strand awaiting CRISPR's guided modifications.

Clinical applications of this framework are already underway. At Boston University's Center for Memory and Brain, psychologists are developing precision recall techniques that combine timed memory retrieval with pharmacological interventions. The approach mirrors CRISPR's two-component system: one element identifies the specific traumatic memory (akin to CRISPR's guide RNA), while another introduces therapeutic modifications (analogous to Cas9's editing function). Early trials show patients reporting decreased emotional intensity while retaining factual memory integrity.

Ethical considerations abound in this emerging field. Critics argue that the CRISPR metaphor oversimplifies memory's complexity, potentially leading to reductive therapeutic approaches. Memory researchers caution that traumatic experiences often interconnect with multiple neural networks – unlike discrete genetic sequences. There's also concern about creating false distinctions between "good" and "bad" memories when many traumatic experiences contain valuable survival information.

The philosophical implications run deep. If memories constitute our identity, does precision editing risk creating discontinuous selves? Some ethicists warn against medicalizing normal human responses to adversity, while others see potential for alleviating crippling PTSD symptoms. The debate echoes earlier controversies about CRISPR's use in human germline editing – both involve fundamental questions about manipulating biological information that shapes who we are.

Technological parallels extend beyond metaphor. Advanced neuroimaging reveals memory traces with increasing precision, much like DNA sequencing technologies enabled CRISPR's rise. Meanwhile, AI-assisted analysis helps identify memory patterns that correlate with trauma severity, providing potential targets for intervention. These converging technologies create what some call a "perfect storm" for memory editing research.

Looking ahead, researchers emphasize the need for nuanced approaches. Unlike genetic editing's binary outcomes, memory modification exists on a spectrum. The most promising therapies aim not for deletion but for cognitive reappraisal – helping patients reframe traumatic events while preserving their narrative coherence. This middle path acknowledges both memory's malleability and its fundamental role in human identity and learning.

As the field progresses, interdisciplinary collaboration becomes crucial. Neuroscientists work alongside ethicists, while trauma specialists consult with molecular biologists. The CRISPR metaphor serves as more than linguistic convenience – it fosters cross-disciplinary dialogue about information storage, retrieval, and modification across biological systems. What emerges may transform not just how we treat trauma, but how we understand the very nature of human memory and resilience.

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025